-

About one-in-five chance of trade battle, says chief economist

-

Looming U.S. midterm elections may prompt Trump to take action

Trade tensions between the U.S. and China pose a greater worry to the global economy than a nuclear North Korea, said National Australia Bank Ltd. chief economist Alan Oster.

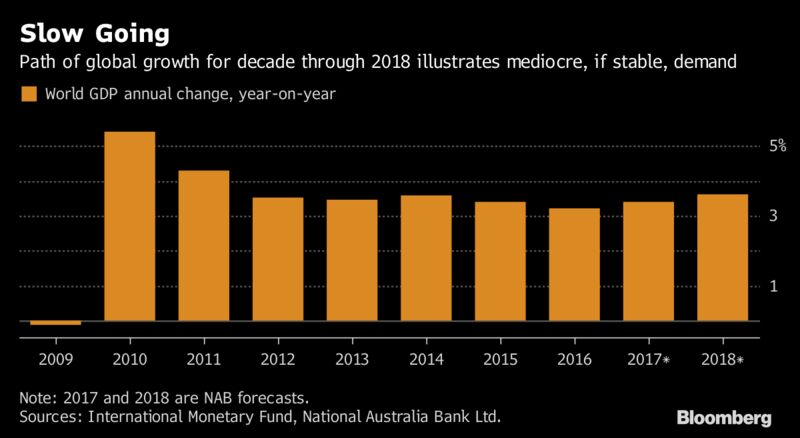

The probability that the world’s two largest economies enter into a destructive trade war is around one-in-five, Oster said in an interview in Singapore. It’s the biggest risk to global growth that’s otherwise chugging along at a decent rate and should rise to 3.6 percent in 2018 from 3.4 percent this year, he said.

“It would kill Asia, and it would kill commodities,” and have flow-through effects to the world, said Oster, a former senior adviser to Federal Treasury in Australia, one of the world’s most China-reliant economies. “Overall, I think the world’s okay. Geopolitical risk is there a lot — who knows about North Korea — but I’m more worried about Trump and China.”

Prospects of trade penalties, flagged since before the start of President Donald Trump’s White House tenure, are taking center stage this week during his first official visit to Asia. In a media briefing with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, during his first stop on the five-nation jaunt, Trump pledged “very, very strong action” and “very soon” on trade relations with China.

What Ever Became of That Trump-China Trade War?: QuickTake Q&A

One reason Oster is cautious: Looming U.S. midterm elections next year might prompt Trump to take action over the summer via executive action that wouldn’t require Congressional approval.

That could derail the somewhat unexpected upswing in global trade, which is probably more due to upbeat growth in China, Oster said. Meanwhile, trade-reliant nations such as Hong Kong and Singapore haven’t been impressing on growth, with more domestic-oriented economies in the region such as Indonesia on a steady and faster pace.

There’s still plenty of slack to be absorbed in Japan and other parts of Asia, as well as in Europe, according to Oster. That should help sustain the already-long global expansion in the near term — leaving more room for meager wage growth to eventually gain some momentum.

A more sound global banking system and stable U.S. growth — estimated at about 2.3 percent next year after 2.1 percent in 2017 — should also support the outlook for the world economy, according to Oster. Trump is likely to win at least a small victory on U.S. tax reform, which should give a modest bump to growth, he said.

Outside of geopolitical risks, the most likely global macroeconomic threat also has China’s name on it.

“If you were looking for something unexpected, it would probably come out of Chinese illiquid balance sheets, where you sort of can’t see what they’ve actually got,” he said. “But in the short term, there’s nothing that really strikes us as saying the global economy should slow big time.”

By Michelle Jamrisko and Andrew Janes